Dir. Joel and Ethan Coen

"What's the most you've ever lost on a coin toss?". By the time the psychopathic contract killer Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem) utters this line in the famous coin-toss scene, he's won this idle conversation with the store clerk (Gene Jones). In fact, he 'won' it further back, when the clerk nervously tells Chigurh that he needs to shut-up shop...in the middle of the day. Take a look at the scene

here, one of the greatest in American cinema history in my opinion.

Through Chigurh's use of the coin we learn an incredible amount about his view on life, and even more after viewing the entire film. But that isn't the only reason this scene is exceptional. The way the tension is created so quickly from an innocuous purchase of some nuts and some fuel is amazing, mostly down to the script and performances, although there is some directorial flair from the great Cohen brothers.

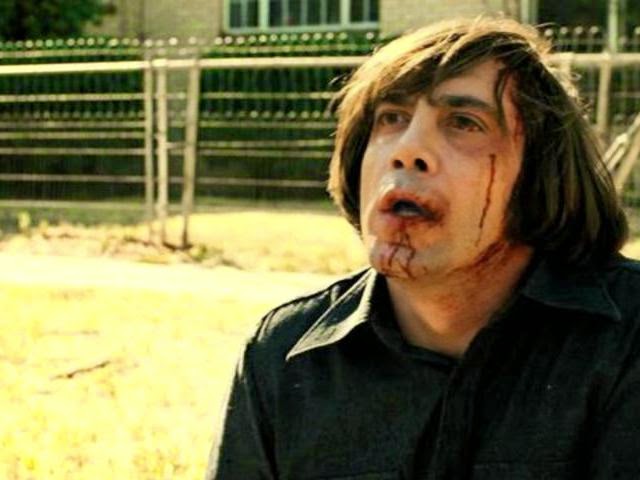

Let's focus on that first, we'll return to the coin in a moment. After a simple inference from the clerk, Chigurh responds "What business is it of yours where I’m from, friendo?". Friendo. It's a word you picture smiling suburban 50's men in golf shirts saying. Chigurh isn't that, not at all. His unusual haircut isn't exactly flattering and he doesn't care a jot, his deep voice, and general rigid, psychopathic demeanor tell us that that word shouldn't be said by this man. In the sentence, it's an end-note to a clear threatening rebuff to the clerk's inquisitiveness.

A few lines later, Chigurh eats his peanuts in silence, staring. As anyone will tell you, if you want someone to feel pressured in a conversation, all you have to do is keep silent, and the other person will fill the gap. This is what Chigurh does here, although it does imply that really he doesn't care. He's thinking his own thoughts about the man in his interesting head. The clerk asks "Will there be something else?", Chigurh responds "I don't know. Will there?", and there's more silence. Who speaks first? The clerk of course.

Another few lines later the clerk loses the verbal duel, as he tells Chigurh nervously that "I need to see about closing". As I mentioned earlier, and as you can see, it's sunny outside, probably around mid-day. Nobody shuts their gas station in the middle of the day. The clerk is intimidated and frightened for his life, and the silence in the conversation makes him let slip his immediate fear.

Clerk: Well…I need to see about closin'.

Chigurh: See about closing.

Clerk: Yessir.

Chigurh: What time do you close?

Clerk: Now. We close now.

Chigurh: Now is not a time. What time do you close.

Clerk: Generally around dark. At dark.

Chigurh calls him out on this, but look how he does it. He doesn't just point out that shutting shop in mid-day is odd, he coaxes the clerk to say it in his own words. As he says "At dark", Chigurh has again won his offensive. Chigurh understands of course why the clerk is afraid, but he's toying with him for his own enjoyment, looking down on this lowly attendant. This is made even more clear later as he asks about the clerks background, repeating the phrase "You married into it". This phrase has so much implication, implying that the man had no initiative of his own, and is less of a 'man' as he marries into the simple business. The Coens here have a little flair after the line "I don’t have some way to put it. That’s the way it is." by Chigurh. As he puts down the empty packet of nuts he's been eating the entire scene, they keep focus on it for a second or two. These few seconds feel like an eternity, as the wrapper unfolds, crinkling and crackling. It's visually showing tension being released, which in some respect is actually happening as the conversation shifts to the coin toss. The scene remains tense of course, but what it does is act as a visual pause. The auditory pauses have remained focus on one of the two, telling us that the performance is important. With the wrapper, it's a break in the scene.

Chigurh asks the question: "What's the most you've ever lost on a coin toss?". The clerk doesn't understand. Chigurh tosses a quarter, slaps it on his hand, and repeats "Call it". The clerk wants to know what he's calling for. Chigurh: "You need to call it. I can’t call it for you. It wouldn’t be fair. It wouldn’t even be right". Well now. What Chigurh has just done is bring in some big themes of life, fairness and what is 'right'. There is of course the subtextual theme of chance. As Chigurh says "It wouldn't be fair", what he means is that if he called this important decision, well he'd be robbing the man of his 50/50 chance of winning. As he says "It wouldn't even be right", we understand Chigurh's belief that a man has a right to call the coin, to decide between life and death. Chigurh, for all his emotionless murder throughout the rest of the film, understand the importance of chance when it comes to life and death. Or maybe it's the opposite? Maybe life and death doesn't come into it, and Chigurh's faith in chance is so strong that he knows he can't call it.

Chigurh: Yes you did. You been putting it up your whole life. You just didn’t know it. You know what date is on this coin?

Chigurh says this in response to the clerk saying " I didn't put nothing up". What the clerk has been "putting up" his entire life is his life as a stake in the game being played right now. These lines are the ones that I think betray how insane Chigurh actually is, as another character will call him later in the film. It's Chigurh who's putting all the importance into this coin, and into the game of life/death.

Chigurh: "Nineteen fifty-eight. It’s been traveling twenty-two years to get here. And now it’s here. And it’s either heads or tails, and you have to say. Call it."

The weight of time lays heavy on this choice. Or at least it seems to do, "You have to say". Why? Because Chigurh has deemed it so. What the early part of the scene has done so well is show us Chigurh's judgment of the man. It's he who's decided that he doesn't deserve life. So now he's playing a game to decide the fact.

The clerk calls correctly, winning "everything". Chigurh congratulates him with a simple "Well done". There's one last bit of interest though. As the clerk takes the quarter as payment, Chigurh tells him not to put it in his pocket, calling it his "lucky quarter". This is true, as it is luck that has saved the man's life. The man asks where to put it, still showing his weakness in comparison to the dominant Chigurh.

Chigurh: Anywhere not in your pocket. Or it’ll get mixed in with the others and become just a coin. Which it is.

"Which it is". Christ this line had me pondering for the entire film! What does it mean? He's saying that the coin is lucky, and special, and shouldn't become part of a uniform group, as then we can't tell which is lucky and which is normal. That's what the "Which it is" means. It means that the coin is in truth only a coin, but it's the importance of the event that's just happened that makes it special, and so deserves to be treated special. It's life in a coin! What's remarkable looking at the scene as a whole, the words life and death are never explicitly stated, only alluded to with "everything" at stake, and the initial question bringing it to mind.

Another great little thing that can be easily overlooked is the fact that Chirurh didn't pay for his transaction. We think he did because the clerk redivided a quarter. The tension of the scene and the event was so great that Chigurh got away with not paying for his fuel, and the clerk himself doesn't notice this. What this tells us is that despite Chigurh's strong belief in forces such as chance, he clearly doesn't think here that paying for his entire purchase is the 'right' thing. Perhaps he thinks that the man winning his life is payment enough? I doubt the clerk would argue!

Let's leave that scene. Near the end of the film, Chigurh goes to the house of Llewelyn Moss' (Josh Brolin) wife, Carla Jean (Kelly Macdonald). Throughout the film, Chirurh has been chasing Moss to reacquire a large sum of money he stole from a drug-deal gone-wrong. Moss is dead at this point in the film, by the guns of Mexican drug-dealers. Chigurh, months later, sits in the house of Carla Jean, confronting her after her return from her mother's funeral. Scene

here. Chigurh is searching for the location of the stolen money, although there's more to it than that. It's a meeting that was hinted at earlier in film, that would occur when Chigurh came to a dead-end in his pursuit of Moss.

She tells him "You don't have to do this". He's a little amused, telling her that everyone says the same. She repeats it "You don't". He flips the coin, "This is the best I can do. Call it.". She refuses, calling him crazy. He repeats it. She responds: "The coin don't have no say. It's just you." She's called the bluff in a way the clerk never did. She's not buying into the game, she knows that his use of the coin is a personal way of offloading his murders into a sense of chance over-all. Chigurh says "I came here the same way the coin did". Another line that had me puzzling at first. What it means is that he believes himself to be a doler out of chance in the same way the coin does, and that the coin is on a journey to eventually be used for this purpose.

I couldn't find an image online unfortunately but we cut to the porch of the house, and Chigurh steps outside, and look at the sole of his boot. It's remarkably subtle but what this tells us is that Chigurh murdered Carla Jean. He's checking for blood on his shoe, which he avoided earlier in the film. This mean that he chose to kill her. Not the coin. His ethos is betrayed, and we see the true psychopath underneath, not that is was that hard to find!

What happens next is important and interesting. Chigurh leaves the house in his car, and nears a crossing. He doesn't realise the light was red, and it hit from the side by an oncoming car. He hobbles out, injured, a bone sticking out under his elbow. He pays a local boy for his shirt, to hide the wound, as he cannot be found by the police. This is the last we see of Chigurh. What it implies is that he was deep in thought about his killing of Carla Jean, and so was hit.

Now I've two interpretations of this. The first, is that there is a force out there that is now punishing him. As he chooses to kill, and not just kill to escape or continue on his path, but to murder an innocent that he could have spared, he is punished by being brutally reminded that he is fallible. Throughout the film he is an unstoppable force, he can be injured, but he always returns. Here, he is punished by chance, and so should learn his lesson that he isn't above chance, he is slaved to it's judgement.

The second interpretation, is that this is chance, but not as punishment. It's just that, chance. Not the mystical force of chance, but just a consequence of events. Due to his lack of focus on the road after the murder, he didn't see the oncoming car, and was hit. Simple as that. What he can take from this is own judgment. So in this interpretation, the world of No Country For Old Men is one of stark reality. There is no overruling force, only events, choices, and consequences.

...I'm not sure which I prefer, but the second interpretation I think is the one that's closest to what Cormac McCarthy, the author of the novel the film is based off, seems to convey in his writings. It can't be overstated how faithful an adaption this film is. Most of the subtext I've described here comes from the script, itself nearly word-for-word from the book. There are filmic touches that enliven the entire story, incredibly so thanks to the masterful Coens, but I must note that it's McCarthy that was primarily being discussed here. If you haven't read any of his books, please do so as I can easily see them being classics of literature in a few decades time, if they aren't already. And of course, if you enjoy No Country For Old Men view the sister film There Will Be Blood (one of my top 5 films), which was filmed in the same location and at the same time. And for McCarthy, read Blood Meridian and The Road, and perhaps watch the adaption of The Road (2009), starring Viggo Mortensen and Kodi Smit-McPhee, directed by John Hillcoat.